History teaches us many things. Not least how we have responded in times of crisis.

"The Lincoln continues to slow down. Its interior is a place of horror. The last bullet has torn through John Kennedy's cerebellum, the lower part of his brain.

"...at first there is no blood. And then, in the very next instant there is nothing but blood...Gobs of blood as thick as a man's hand are soaking the floor of the back seat..."

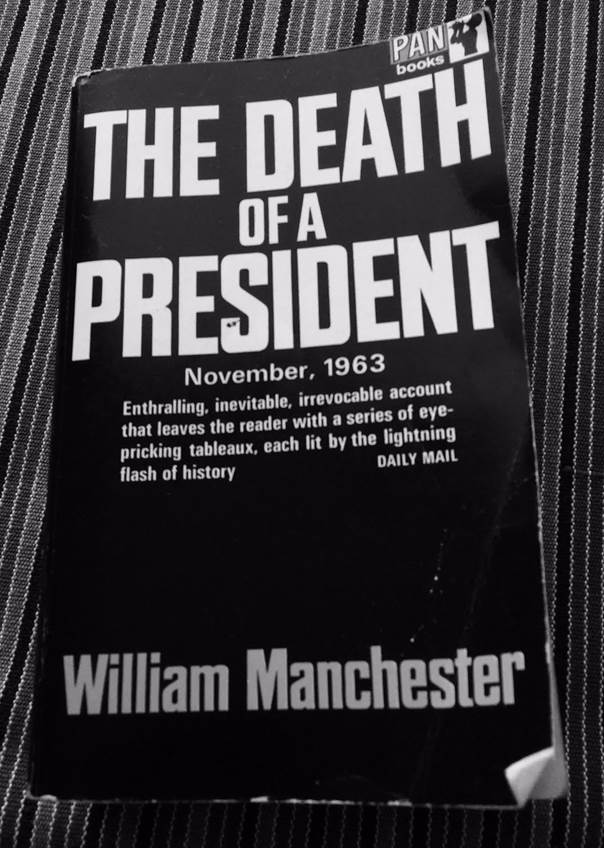

I recently read The Death of a President, William Manchester's brilliant unflinching account of the events leading up to and the aftermath of the assassination of John F Kennedy in November 1963.

You can see the Wikipedia entry about the book here.

Everything is in here, from the paintings on the wall of the hotel room where Kennedy spent his last night alive to the layout of the emergency room the president lay in at Parkland Memorial Hospital as doctors tried vainly to save his life.

And amidst the detail, there's some interesting insights into communication at a time of crisis - particularly in terms of the crossed lines and Chinese whispers that occur at a time of shock and trauma as people come to terms with events both sudden and surreal.

What's surprising about The Death of A President is its revelations about how some of the most powerful people in the US were paralysed by indecision and confusion in the wake of unimaginable events.

One example comes when Air Force One prepares to leave Dallas two hours after the shooting.

Effectively, Lyndon Johnson - the Vice President - is now the man in charge, but most people in the travelling party are still in shock and can't believe that Kennedy is no longer President.

Johnson has given the order not to take off, he wants to take the oath of presidential office while in Dallas, but no-one manages to get that order - from the most powerful man in the world - to the captain of Air Force One despite the fact they are on the same plane.

When the casket containing Kennedy's body returns to the plane the pilot starts the sequence for take off.

It's only after a series of mistakes and miscommunications - involving everything from Lady Bird Johnson's left luggage to confusion over whether the press should be on the plane - that the jet stays on the ground. Nothing to do with the new President's orders.

And after this, events take on a tone of grim farce. A photographer and a judge have to be found for the swearing-in while at the last minute someone realises there isn't a bible and the late President Kennedy's treasured copy has to be fetched from his cabin.

And in the fevered atmosphere outside the plane rumours and misinformation - much of it spread by media outlets trying to make sense of rapidly developing events - abound. Lyndon Johnson is injured and staying in Dallas, one of the body guards is dead, Kennedy was shot from the front not the back - this last myth is credited with beginning the conspiracy theory industry that later sprang up around the assassination.

It shouldn't be surprising that great trauma and shock produces confusion and disarray no matter how powerful the people and institutions involved. But somehow we expect our leaders to be totally resilient no matter what history throws at those in charge.

We forget that people react in all sorts of ways at time of crisis. Later on their actions seem strange or random to us.

For a vivid example, look at the pictures taken at Johnson's swearing-in or at the footage of Kennedy's body being taken off Air Force One on return to Washington five hours after the shooting.

Look carefully and you can see dark patches all over Jacqueline Kennedy's pink Chanel suit and her tights. Those dark patches are the dead President's blood.

She refused to change her clothes, no doubt still in shock, but also as an act of defiance. She wanted the world to see what the assassin had done to her husband.

Will Mapplebeck is Strategic Communications Manager for Core Cities UK