GUEST EDITOR: Ben Proctor of the Likeaword consultancy.

What should press offices do when the printing presses go quiet? In this post a plan for revolution is drafted. But there's still a role to play for communications people if they adapt.

A modest proposal.

I think press offices in the public sector are a bad idea and that we should get rid of them.

I am not some wild-eyed tax-reformer wanting to end all spend on communications.

I am not prejudiced against ex-journalists, PROs and other assorted “spin doctors”.

I am, in fact, in favour of effective and well resourced communications.

In fact I believe I may be on record as having said that people make better decisions with PR professionals in the room.

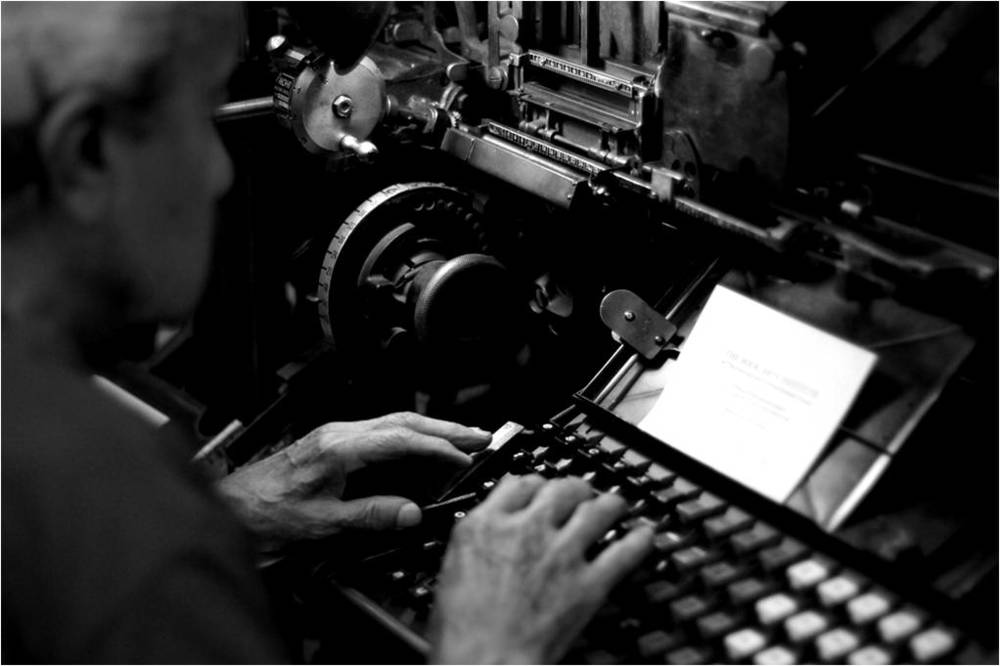

Press offices though, it seems to me, are 20th century solutions to a wider problem. They were developed with 1950s technology and have evolved slowly. We have better technology now. It may be time to scrap this solution and design a new one from the ground up.

What is a Press Office?

Typically journalists get access to a special telephone number staffed by ex-journalists or other professionals who understand their needs and will answer their questions in a timely manner. Those people will also generate stories from within the organisation, tailor them to be suitable for journalists and provide them in a suitable format. When I started this format was a piece of paper dropped in an envelope (and I’m really not that old) but these days it is likely to be an email, or access to a photo-shoot, or just a photo.

This is a much better service than you, the citizen, can normally expect to receive. Your phone call may be queued for a long time, simple issues are likely to be resolved speedily but more complex answers are likely to take some time to filter through to you.

Why do journalists get such a superior service compared to you or I?

Because they are special.

They are special in two main ways:

- they have access to media which are, on the whole, trusted by their audiences

- they have an accepted role in society of investigating and holding the powerful to account

The cynical might argue that one way press offices are used is to neutralise the effects of both of these aspects. In so far as it is true it is an even stronger argument for removing them.

Things are changing

The media are becoming more complex and fragmented. The front page of a national newspaper remains a very prominent place to be but in some areas local paper circulation has crashed and in all areas media are having to find new business models. These models rarely seem to mean more journalists. For a long time and with notable and important exceptions local media tended to be clients of the local state rather than fierce watchdogs of it. It is easier for citizens to create their own media, whether these are hyperlocal blogs, mischief making facebook pages or simple twitter accounts. Journalism is evolving into a practice heavily embedded in a wider digital community.

We have infinite spaces. In 1997 as a local council press officer I relied on the local media almost exclusively to tell local people what we were up to. We did not have a website. We had only recently embraced email. Journalists had two sources of information about what we were up to: committee reports and me. They used both heavily. These days we can open up our organisations to a much greater degree. We can publish an unparalleled feed of data and make it useable. We can put every report, every draft and even every email up and open. And anyone can ask for anything. Mostly we have to hand it to them.

We have levelling tools. I never subscribed to the idea that journalists should be compelled to route their enquiries through the press office. I thought we were there to help not to mind the gate. Not all of my colleagues agreed. I remember explaining to a planning team that journalists were at least members of the public so they should feel able to answer their questions in the same way they would answer any other enquiries. The more we get people out into digital (and physical spaces) engaging directly with the public realm, explaining their work and listening to feedback, the less we need to use media to communicate that message.

What would we do instead?

We would replace press offices with a digital space and give citizens the same privileges to ask questions and demand explanations that are afforded to journalists. Not reducing journalists’ access just raising everyone else’s.

We would go headlong into open data: publishing everything we can in an easily usable format under an open licence. We would support citizens, including journalists, to interrogate and investigate this data. We would respond to what they (and what we) find hiding in there.

We would stop issuing press releases. Indeed we would end the whole concept of identifying news that the organisation feels is important, polishing this into acceptable copy, creating photo-opps and launches, and then pushing it out to the media. Individual professionals and politicians might, in the normal run of things, suggest that, say, teenage drinking was a problem or that cycle journeys should be increased. They could use digital publishing platforms to share these ideas. They could point to the published data for evidence. They could collaborate with a wider community to identify solutions. These could be discussed and debated and reported by journalists, other professionals and citizens as a whole.

There would still be a role for corporate comms professionals. A massively important role, to develop and build communities around the data. To train, and encourage, mentor and support professionals (and politicians) to play more active roles in public spaces. To tell the core stories in the organisation so that stakeholders understand what the organisation is about, what is important to it and what it is seeking to achieve.

And to be honest I probably wouldn’t do this tomorrow.

It would certainly be a bold move right now.

But we should start planning.

Ben Proctor is a former public sector head of communications, a member of the Chartered Institute of Public Relations and an associate member of the Emergency Planning Society. He runs the likeaword consultancy which helps organisations to use communications to manage relationships and change behaviours.