The most terrifying thing about pestilence is its power to terrify. In reputational terms, any plague has a mighty PR punch that far exceeds the reach of the disease itself – and often brings out the worst in people. That demands responsibility on the part of PR professionals.

By GUEST EDITOR Alan Taman

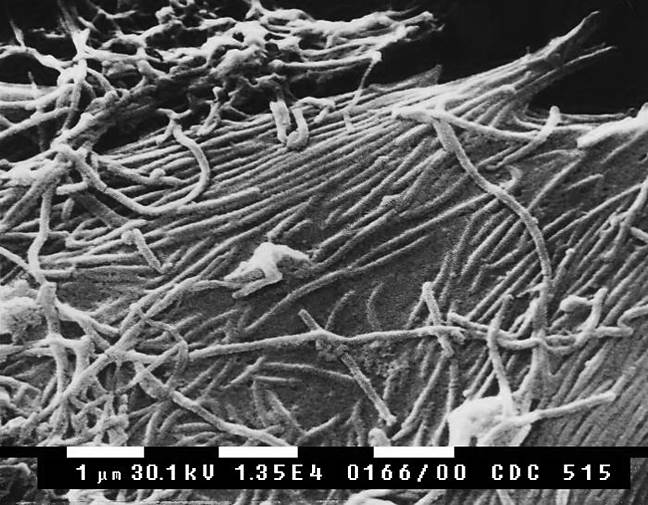

Case in point: ebola. A haemorrhagic fever with no vaccine or cure. Meaning if left untreated victims will rapidly dehydrate and die through organ failure, shedding the virus in their body fluids as they do so. Which will infect new victims through any mucous membrane or broken skin. But not, thankfully, via airborne droplets, as in flu, or via parasites, as with bubonic plague (which could also spread via droplets; ‘Atishoo, atishoo, we all fall down’ – grim, some nursery rhymes).

The west does not cope well with serious infection that cannot be stopped with a magic injection and can be caught from another person. Once we are without the reassurance of modern-day invincible medicine, ancient fears and prejudices are never too far behind. So it is proving with ebola: ‘it’s extremely infectious and contagious’, screamed BBC1 TV news. Pandering to the plague myth. Contrasted with ‘It can only be caught through direct contact with bodily fluids’ from a health expert on the BBC News Channel less than 20 minutes earlier. Now which of those two statements is the most responsible, and why? And which will have reached the greater audience? No points for ducking the plague panic, guys.

I used to be frustrated, at times, with the NHS’s ponderous responses to complex questions. But the health professionals had their reasons. As they do now. Fear of ebola can do almost as much harm as the diseases itself, at least in the UK. We are not likely to leave victims out in rural areas for days without treatment, nor will the family of anyone unfortunate enough to succumb be buried by relatives who handle the body as part of the burial: which is what has been happening in Africa. Mortality will be less, though how much less is simply unknown. We are far more capable of isolating an outbreak. The NHS is very good at that sort of thing: that is true.

What people are not good at is in facing a vague yet probably fatal threat. They tend to respond by blaming strangers, bad behaviour, or an enemy – then treat all of the blamed group as badly. A close parallel with ebola, as a disease, used to be yellow fever, or ‘Yellow Jack’, now curable. Its outbreaks in the nineteenth century caused mass responses more at home in the ninth: astonishing examples can be found here. Threats (and acts) of violence, superstition, prejudice and bigotry far outstripped the disease’s course. Yet this was in an industrialised, modern state.

PR has a critical role to play here, for any agency given public responsibility in fighting any serious disease. Having the facts is not enough (WHO’s seem the best, so far): PR must also fight the fear. In the case of ebola, that could easily tip into xenophobia (already with us?) and people running away from a shadow when all they had to do was wait for the clear light of reason – and the NHS – to reach them. That’s our job.

Alan Taman is currently researching and campaigning for better training and standards in health journalism and PR. He is a member of the National Union of Journalist’s Public Relations and Communications Council. He can be contacted on: healthjournos@gmail.com or via his website. You can follow the campaign on @healthjournos on Twitter or on www.europeanhealthjournalism.com

image via Wikimedia Commons